Mysterious Dumps, Thumps, Cruits, Crotts and Crwth and Jumps

So, is there any evidence that the dump was a harp technique with possibly Irish or Welsh roots?

Synopsis and thesis: It seems to me that a clear audible resemblance exists between several lute dumps in the Marsh manuscript and some of the pieces in the Robert ap Huw manuscript for the Welsh harp. This could be significant because of the lack of information on the English dump as a genre and the remarkable uniqueness of the music recently deciphered in the ap Huw MS. The following notes seek to provide a summary of some of the aspects of that problem as well as of the ideas and avenues already proposed on the topic.

Some of this research may be useful in a further more detailed study of the dumps contained in the Marsh Lute Book, the identification of their author, as well as the provenance of the MS. It might also reveal just how much we don't know about that manuscript and the interaction between court and other musicians, harpers and lutenists in general.

Note: the following are preliminary notes to a formal essay on the subject rather than a finished product. Take it as such, and please let me know if you have additional information or corrections to make to my research. Several brains are almost always better than one. You can simply email me your comments and I will put them in the comments section attached to this collection. If you are a registered Django user, simply log in and click on the Add comment link to do the same.

Notes on this revision: some of the WEB links I originally quote have now disappeared unfortunately. I tried to correct the ones I could find, but I am intentionally leaving the dead ones just in case they pop up somewhere. The main change from the original draft is the connection between the Irish tiompan and the Welsh crwth, and therefore a tighter link between the playing technique of the crwth and the formal characteristic of the dump, with an alternating bass drone on two strings done with the thumb. The same technique on the harp would probably use an alternating thumb/index finger also on two bass strings.

Indeed, several claims to that effect - i.e linking dumps to the harp - have already been made in the past, although I have to say the evidence presented cannot be deemed entirely convincing. Oddly enough perhaps, a good deal of information seems to be provided from Shakespeare rather than more genuinely Irish sources.

I. The musical form approach

But first, was the dump a genre, a technique or a dance? We find a somewhat tentative answer in William Chappell's book Old English popular music where the dump is defined in the following manner:

"The dump is commonly described as a slow dance but nothing exact seems to be known about it."

Note that while presenting the dump as melancholy, slow dance tune, the same author quotes Shakespeare against its own theory while discussing the popular tune Heart's ease: Shakespeare mentions Heart's ease in Romeo and Juliet, act iv., sc. 5 :—

Peter.—" Musicians, O musicians, Heart's-ease, heart's-ease: O an you will have me live, play Heart's-ease.

1st Mus.— Why Heart's-ease ?

Peter.—O musicians, because my heart itself plays My heart is full of woe . O play me some merry dump, to comfort me."

Clearly, in Shakespeare's time, dumps could be merry or doleful. Furthermore, the author cites examples of dumps in duple (Lady Carey's dompe) and triple meter (Power mane's doumpe [Poor man's dump]) that would seem to invalidate the idea that the dump was a dance at all, unless we consider a resemblance with the continental "bransles" or brandes that could also be either slow or gay, in duple or triple meter (4/4 or 9/8 or 6/8). By far, the most popular lute dump today is the Queen's dump, a duet by John Johnson that cannot be possibly construed as a slow melancholy piece. From that point of view, the dump is clearly different in nature from the Irish O-Hoane which is a cry of desperation, identifiably Irish and always painfully sad.

Perhaps some level of confusion in later days developed between the dump and the O-Hoane: pleading the case of the Dump as a typically melancholy Irish tune is a remark that Irish women would sing the tune on battlefields while recovering the bodies of the dead, but this remark comes to us from a point in time well after the peak of popularity of the dump as a genre, during the Civil War:

Píobaire, An Volume: 6 | Issue:1 | Page: 22 | Date: 2010

After this air is played, the Provincial Cries (Nos. II, III, IV, and V.) are performed in succession: then (No. VI.) [i.e., Gol na mna ‘san ar] a melancholy tune, or dump (which is said to have been sung by the Irish women, while searching for their slaughtered husbands, after a bloody engagement between the Irish and Cromwell’s troops) follows; and the whole is supposed to conclude with a loud shout of the auditors, meliorated by affliction.

Closer in time to the dump tunes found in the Marsh lute book, is a piece from the Fitzwilliam virginal book that seems to be more on the merry side: see http://web.me.com/whistler4/DavidsMusic/Recordings/Entries/2008/5/19_The_Irish_Dumpe_files/The%20Irishe%20Dumpe.mp3

The title is cryptic: is this called the Irish dompe because dumps were more particularly Irish, or is this a particular Irish form of a more generally widespread genre of music, like the branles de Poitou and de Bourgogne were local adaptations of the "generic" branle? Furthermore, there are doubts about the authenticity of this tune's Irishness:

The English musicologist Chappell (1859) quotes Sir Robert Stewart, who, in writing on Irish music for Grove's Dictionary, doubted the 'Irishness' of the tune. A melody by the name of "An Irish Dumpe," signifying a lament or slow air, appears in Thompson's Hibernian Muse of 1786, though the tune is a version of "The Lament of the Women in the Battle" (Gol na mBan san Ar). The melody also appears in Hoffman's 1877 arrangement of tunes from the Petrie collection. Chappell (Popular Music of the Olden Time), Vol. 1, 1859; pg. 85.

II. The tiompan lead

The Musical times and singing-class circular, Volume 52, dated 1911 brings some interesting information in the form of a controversy between Francis Galpin and WH Grattan Flood, author of "A History of Irish Music" and ardent defensor of Irish musical genius who intends to correct Galpin's account of the origins of the Irish harp. He writes:

As to the Ullard Harp, I myself examined it some twenty years ago, but I relied mainly on Sir Samuel Ferguson's description as given in 1834, as did also Dr. Petrie. The photograph evidently shows a forepillar, and the instrument I dare say may be classed as a quadrangular Cruit. However, I beg to point out that Mr. Galpin is in error in stating that the Irish Bards (no doubt he means the Irish Minstrels, not the Bards proper, who were poets, not musicians) ' adopted the harp from their music-loving neighbours'—that is, the English —in the 11th century. As a matter of fact there is distinct mention of the Irish harp in the 9th century, and there is a beautiful representation of the instrument on the shrine of St. Moedhoe, an exquisite bronze carving of the 9th century. An Irish entry fixes the date as prior to the year 888. Again, Ottfried von Weissenberg, circa 855, a pupil of the Irish monks of St. Gall, alludes to the harp, while it must not be forgotten that Caedmon was of Celtic descent. I may also add that the Irish of the 9th century had 'harp bags' of otter skins, and surely it is well known that St. Aldhelm, Bishop of Sherborne, was taught the harp by Irish monks, as was also St. Dunstan. The Irish Tiomp (diminutive 'tiompan ') gave the cue for the English Timpe, and the Dump. Nor must it be forgotten that there is mention of the Fidil in an Irish tract of the 7th century, while there is still to be seen a sculptural figure of a man playing the bowed cruit at Lough Currave, Co. Kerry, dating from the I2th century.

WH GRATTAN FLOOD

Flood's remark takes in a totally new direction: dumps are neither a dance, merry nor melancholy. Rather they are the expression of a native Irish instrument: the tyompan or tiompan.

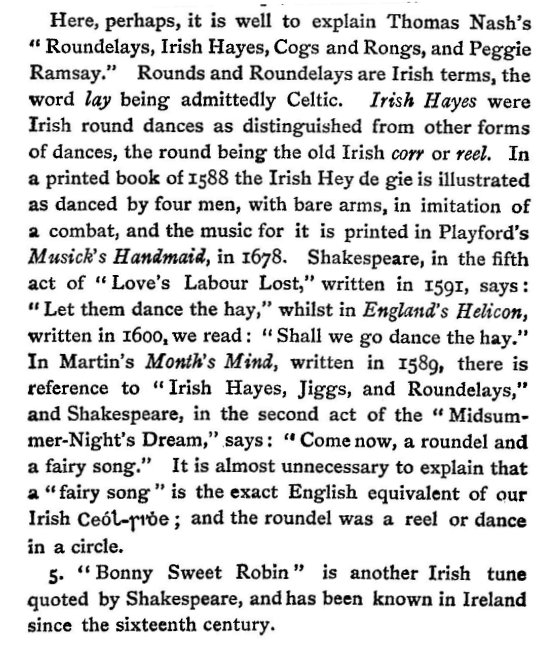

Probably following Flood's assertion, Alfred Percival Graves drives very much the same point in an article for Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society dated 1967:

The Tumpany clan were tympan players - players on the instrument that gave its name to the tune played to it - i.e. the Dump. Hence the expression "doleful dumps".

Grattan Flood develops this tiompan theme more in detail in his book The History of Irish music:

Unfortunately, Mr Grattan loses me in the immediately following passage with its excessive enthusiasm for all things Irish -- the word "lay" (and its derivations virelai, rondelai) is much more likely to come from the French "lai" than from the Irish or Celtic. The word "roundel" similarly comes from the French dance called the "Ronde" which children still do there at school It is a dance in a circle, hence the name:

For a transcription and lyrics of the Peg a Ramsay tune, see this link.

Someone whose identity I was not able to identify on The Fiddler's Companion quotes the passage above by Grattan Flood extensively and adds to it some more details about the technique of playing the tiompan and its connection with dumps:

In fact, according to Flood, it referred to the music of an ancient Irish harplike instrument, the "tiompan" or timpan. The timpan was also popular in England in the 15th and 16th centurys, and the words "dump" and "thump," which mean to "pluck" and "strike" the timpan entered the English language, originally in connection with the instrument. Thus Shakespeare's reference to a "merry dump" is explained as descriptive of a technique of playing or a type of sharp musical attack (See "Dump").

So what is a tiompan?

According to Wikipedia's article:

An Tiompan Gàidhealach

The tiompán (Irish) or tiompan (Scottish Gaelic) was a stringed musical instrument used by the Gaelic musicians of Ireland and Scotland and probably therefore the Isle of Man.

The word 'timpán' was of both masculine and feminine gender in classical Irish. It is theorised to derived from the Latin word 'tympanum' (tambourine or kettle drum) and 'timpán' does appear to be used in certain ancient texts to describe a drum.

The adjective 'timpánach' referred to a performer on the instrument but is also recorded in one instance in the Dánta Grádha as describing a cruit.

The feminine noun 'timpánacht' referred to the art or practice of playing the tiompán.

In modern Irish traditional music, the word tiompan was used by the late Derek Bell, after Galpin's theories, to refer to the hammered dulcimer.

Tiompán (or hammered dulcimer):

There are only vague descriptions of this ancient instrument. There are also many opposing theories on what the tiompán actually was, from a drum to a stringed instrument. An old Gaelic dictionary that defines it as:

tiompán

nm. g.v. -ain; pl.+an, cymbal, tabor

What Derek calls a tiompán is a modern day hammered dulcimer. The dulcimer is most likely the modern equivalent to the tiompán.

The tiompán could be one or several of the following:

You have to admit, this is not very conclusive: drum, harp, dulcimer? This indecision is consequential because it is impossible from that basis to get any idea about the technique of playing used and how this could have inspired the Dump as a musical form. Whether it was played with hammers, fingers, bow or plectrum would have some incidence on the style of music produced.

Eogan Og writes on the Minstrel bulletin board:

There was also an instrument called the "timpan" or "tiompan." It's identity is uncertain, but we know it was a stringed instrument with 3 to 8 strings, played with a bow, plectrum, or fingers.

I quote from Farmer:

". . . the cruit, clairseach, and timpan were the art and ceremonial instruments of the Irish and Scots, being invariably found in the hands of musicians of high standing. All 3 instruments were furnished with metal strings.

Erick Falc'her-Poyroux in his extensive research on the old music of Ireland, notes that:

Breandán Breathnach estime pour sa part que le nombre d'instruments dont l'existence est attestée est beaucoup plus restreint. Le timpán serait sans rapport avec le tambourin appelé tympanum en latin et cité par Giraud de Cambrie ; il préfère y voir un instrument à cordes, ancêtre de la famille des rebecs et des violons, se fondant sur une description poétique de la Foire de Carman extraite du Book of Leinster, manuscrit datant vraisemblablement du XIIe siècle.(BREATHNACH Breandán, Folk Music and Dances of Ireland, Cork, Mercier Press, 1977 (1ère éd. 1971), pp. 6-7)

The same author makes an important remark on the politics of music in Great Britain during the time of Elizabeth and later:

C'est donc sous le règne Tudor (1495-1603), et plus précisément sous celui de la Reine Elisabeth 1ère que fut publiée en 1564 une loi interdisant les musiciens itinérants sous le prétexte qu'ils rendaient visite à leurs hôtes moins pour faire de la musique que pour fomenter quelque rébellion. Comme nous l'avons dit, cette volonté d'éliminer les harpeurs ne visait en rien la musique car l'on sait que la Reine Elisabeth entretint elle-même un harpeur du nom de Cormac MacDermott entre 1590 et sa mort en 1603, date à laquelle il passa au service de son successeur, Jacques 1er (vide O'NEILL Francis, op.cit., 1987 (1ère édition 1913), p. 28.). C'est également de cette époque que datent les premières mélodies irlandaises incluses dans des collections anglaises, ainsi que le premier livre comportant des airs arrangés pour la harpe irlandaise.

Pourtant, en vertu d'un arrêté pris en 1654, durant la période qui vit Cromwell dominer l'Irlande, les musiciens furent obligés d'obtenir un permis de circulation spécifiant leur religion pour voyager. Les lois pénales qui s'ensuivirent (à partir de 1695) ne firent rien pour faciliter la vie de ces instrumentistes autrefois vénérés de l'Ordre Bardique, désormais réduits au rang de musiciens itinérants.

Indeed political pressure on the harpists increased significantly in the later 16th century so much so that a young man sought to collect in manuscript a repertoire heretofore confined to oral tradition alone. What lead Robert ap Huw to work that unique compilation of music from the preceding 3 or 4 centuries around the year 1613 may never be known but no doubt like Thomas Ravenscroft at the exact same time, he was likely to feel that the music he was collecting was in grave jeopardy of disappearing forever. That very same period, in the last decade of the 16th century and the first of the 17th saw the complete disappearance of the dump as a genre of music suitable for the lute.

The political dimension is hard to rule out in the case of our story and Gaelic music in general, first in the 16th century, then in the early 20th century, when Grattan Flood was emitting some fairly brash comments barely a few years before the Irish revolution. Those comments were later repeated and quoted as if they had a solid historical foundation whereas they may only have had nationalistic fervor.

It must also be said that if the Arthur of Arthere's dump is indeed King Arthur, the arthurian legends were close to the heart and mythology of the Welsh and at a time when Wales was still semi-conquered territory, Arthur would have stood as a powerful symbol of resistance against the Saxon invadors who came from the East. The first datable mention of King Arthur is in a 9th-century Latin text.

The Historia Brittonum, a 9th-century Latin historical compilation attributed in some late manuscripts to a Welsh cleric called Nennius, lists twelve battles that Arthur fought. (Wikipedia)

Thinking about it, the association of a virtuoso piece of music in the Gaelic style dedicated to a mythical Celtic king might have seemed a very hard sale at the English court with its Anglo-Norman, anglican and continental cultural influence. If indeed this was the case, whoever wrote that music had a large amount of bravado both musically and politically. Unfortunately the early history of the Marsh lute book is lost to us as this would have helped shed more light on the personality of the scribe and his contacts in the musical sphere of his day. However we should remember that harpists were - and are - still employed by the Royal household:

There appears to have been a tradition of apprenticeship among the court harpers in the early seventeenth century. From July 1618 Philip Squire received 30 pounds a year to teach Lewis Evans, a child of great dexterity in music, to play on the irish harp and other instruments. Further privy seals show that Squire continued to teach Evans and provide his maintenance until Evans received his owen post in 1633.

The Consort Music of William Lawes, 1602-1645, By John Cunningham

III. The Robert ap Huw temptation

There remains one type of evidence to explore that might connect the dump as a musical form to the Gaelic harp, but it also greatly suspicious for two reasons: first, there is no explicit connection made between those two edlements in the original source, and second, while the authenticity of the source is unquestionable, its exact interpretation is still a matter of debate. That source is the Robert ap Huw manuscript, a collection of Welsh music for harp in tablature notation. Unfortunately it is the only surviving document using that tablature format, and until very recently it was left undeciphered and the notation system remained mysterious. Pioneering work on the manuscript was done by Paul Whittaker in the mid-1970s. A copy of Paul Whittaker's dissertation is available online. A complete facsimile of the ap Huw MS is available on Greg Lindhal's pages, together with much supporting information, links, a bibliography, etc.

One important contributor to the understanding of that collection of music is Peter Greenhill, who put the details of his research online. Regarding the type of instrument used to play the ap Huw music, he remarks:

It is argued that the pieces in the manuscript were played not only on the harp (probably in a variety of forms), but that the crwth was commonly used as an alternative. It is advanced that the timpan provided a further alternative. It is noted that in the field of contemporary stringed instruments it is not possible to delimit the range of instruments used.

The Crwth

W.K. Sullivan gives a very interesting description of the crwth in the Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society

(pp.69-70). That instrument seems to have been designed to produce the kind of drone effect found in most dumps :

W.K. Sullivan gives a very interesting description of the crwth in the Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society

(pp.69-70). That instrument seems to have been designed to produce the kind of drone effect found in most dumps :

A bowed instrument, called a Crwth, was still in use in Wales in the eighteenth century. Mr. Dairies Barrington, in a letter to the Society of Antiquaries in 1770, gave a description of it, illustrated by an engraving. According to Mr. Barrington's account, the Crwth had six strings, two of which projected beyond the finger board, one of these being touched by the thumb; the bridge was perfectly flat, so that all the strings were necessarily struck at the same time, and afforded a perpetual succession of chords. The bow resembled that of a tenor fiddleThe instrument was then almost extinct, there being but one person 1n the Principality of Wales, John Morgan, of Newburgh, in Anglesea, who could play upon it.

Sullivan continues with another description of another type of crwth:

The Crwth described by Sir John Hawkins in his History of Music differs in many respects from the one just mentioned. According to Sir John Hawkins' account, this instrument was twenty-two inches in length, and one inch and a half in thickness ; it had the same number of strings as the one described by Daines Barrington ; the bridge is also placed in an oblique direction; but one of its feet goes through one of the sound holes, which are circular, and rests on the inside of the back of the body of the instrument; the other foot, which is proportionately shorter, resting on the belly before the other sound hole. ‘Four of the strings pass down the finger-board and under the end-board; but the fifth and sixth, which are about an inch longer than the others, do not pass over the fingerboard, but are carried outside it about an inch, so that they could be freely struck through the apertures for the hand, by the thumb or finger armed with a quill. All the strings pass under the end-board, and are wound up by wooden T pegs, or by iron pins, turned by a wrest like those of a harp.

Finally, Sullivan ties the Welsh crwth to the Irish Timpan:

It is singular that Giraldus makes no mention of the Crud being used in his own country, though he mentions that a very similar instrument was in use in Ireland, under the name of Timpan, for the evidence given in the Lectures fully proves that one kind of Timpan was a bowed instrument.

According to the MOCH PRYDERI'S WEB page, the crwth was specifically Welsh, and it implied a particular technique of playing, using the thumb for the 2 extra-strings off the finger board:

Later two more strings seem to have been added for from the 11th C. on it is referred to as having 6 strings. One poem even mentions that 2 of the strings are "for the thumb." As Marcuse points out, the 2 extra strings seem to have been drones, off of the fingerboard, that the thumb could reach while bowing.

This could be significant, since many of the dumps represented in the Marsh lute book involve the kind of drone effect played by the thumb over two strings, not unlike modern finger picking.

You can see a modern player on the crwth here. In this case, he uses a bow, but the ancient players are said to have plucked the instrument's strings.

So the style of playing the crwth could be possibly adapted to the mode of playing the lute, with an alternating thumb motion on two bass strings, which would be much more unlikely if the instrument were played with hammers for instance.

Formal considerations on the Welsh music for harp or crwth:

Regarding the formal quality of the music in the ap Huw MS, Mr Greenhill notes that "certainly the music so far has not been identified as belonging to any familiar genre." He furthermore remarks that:

Although variations are common throughout most of the text, the pieces do not lend themselves to being characterised as structured on the air-with-variations principle. Perhaps the most unfamiliar feature is that most of the pieces are extraordinarily long.

This seems consistent with at least some of the dumps found in the Marsh lute book, Arthur's Dump being perhaps the best example.

Auditory evidence

I come to the end of this presentation with the most elusive and yet convincing in my mind tie between the music for harp in the ap Huw MS and the dumps in the Marsh lute book, that is the audible representation of the music in the ap Huw MS. Of course I would expect many people to disagree with me on any resemblance between the two styles.

There is a presentation page for several live interpretations of the ap Huw MS music at http://www.dafyddapgwilym.net/video/index_eng.php, but I would like to engage you to visit more particularly the following two renditions, extremely ably played by Bill Taylor. The first one is a rendition of the tune entitled Gosteg Dafydd Athro (Robert ap Huw manuscript, p. 15) and the second one is Caniad San Silin (Robert ap Huw manuscript, p. 69)

IV. Back to the dance

What was the dump? Was it a melodic line sung by Irish women on the battlefield, a dance akin to the branle in its metrical variety, a dance form inherited and borrowed from the Venitian paduan, or a style of playing the harp or the tiompan on metal strings? There is one final - or additional - option perhaps. Could the word "dump" be a slight deformation of the word "jump"? Just like the branle's definition comes from the swaying movement of the dancers from side to side rather than any strutural characteristic of the music itself, perhaps the dump was characterized by a particular form of syncopation that indicates the time for a jump, not unlike the fifth step in a galliard. Indeed, both Arthur's dump and Lady Carey's dump both have that syncopation on the first beat that seems to act like a signature for the recognition of that musical style. The jump would be on the first beat with the landing on the third.

This is pure speculation on my part, but one argue that the volte is similarly named after a specific movement of the dancer's body presumably at regular fixed intervals in the music. Finally here we would find some solid ground for analysis and understanding: if we can find the same form of syncopation, of rhythmic signature in both the remaining repertoire of dumps for the lute and in the ap Huw music the case for a connection between the two repertoire could be on reasonably firm ground. It is what I think I hear in Arthur's dump, Lady Carey's dump, and the Gosted Dafydd Athro pieces, as well as perhaps the Queen's dump by Johnson. This will require a much more formal study however, beginning with a transcription of all the dumps in the Marsh lute book.

Rhythmic signatures

The similarity between the rhythms of the Lady Carey's dump and Arthur dump is quite obvious with their first very distinctive syncopated beat. John Johnson's Queen's dump also shows a syncopated pattern over a two-bar period, but without the missing note on the first beat of the 2 bar period. The rhythmic pattern in the first bar of the Queen's dump matches exactly the pattern of the second bar of Lady Carey's dump. If there is a common rhythmic signature between all three pieces, it might be in the missing second beat every other bar. Both Lady Carey and Arthur are the earlier pieces in terms of composition.

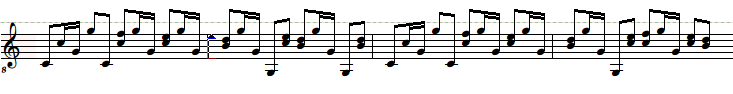

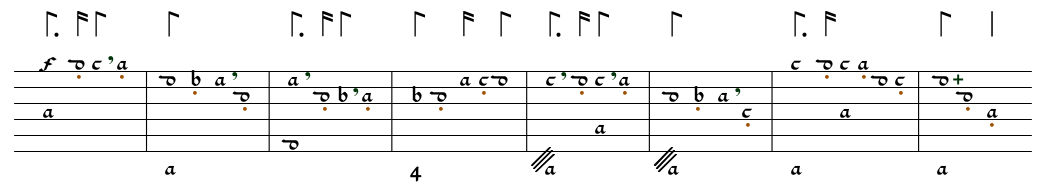

Arthur Dump first bars:

Arthur Dump - melody:

Lady Carey's dump first bars:

Queen's Dump duet first bars:

V. The Marsh L.B. and Dumps

Nothing is known of the Marsh lute book before its acquisition by the archbishop in Cambridge around 1700. I let you decide if this represents 100 years or an eternity of uncertainty. It is not at all implausible that the MS may have had a Welsh or Irish origin. However, like most manuscript collections of the period, it is a compilation of standards of the time, relatively independent of its geographical origin. The somewhat unusual presence of a relatively important number of dumps may - or given the large number of pieces may not... - be significant. Still, the high musical quality of the dumps in the MS beg for further inquiry into their origin as well as the circumstances of their demise. Politics, tradition, as well as instrument making skills and playing techniques all partake of that history in ways that are difficult to disentangle, which makes this particular topic all the more fascinating.

Post remarks

Incidentally, I was very pleased to discover in the course of this exploration the recording by Andrew Lawrence King of Chorégraphie, a collection of French Baroque pieces including some for lute on the harp like the Chaconne by the vieux Gautier. I highly recommend you relax to it. It is on Spotify as well I am sure as in many other places like Amazon.com. Quite a successful piece of musical cross-pollination that! Musicians are natural borrowers and thieves like magpies. Crazy as my hunch may be, what would be extraordinary in my opinion is that no dialogue whatsoever took place between the very well established and flourishing harp traditions in Wales and Ireland and the British lutenists in courtly circles. Putting one's finger on an exact instance or proof of that connection is another matter. But like the Higgs boson, it has to exist and like the most famous of the Gaelic bards, we are only blindly striking the strings for not seeing it.

log in and use the Add Comment button on this page.

Thank you for your ideas and remarks!

No animals were harmed in the writing of this essay.